by Sidik Fofana

There was a time when quality of education depended only on the school teacher and his or her class room. This could have been pre Civil War. It could have been in the days of the colonies. It could have even been before Christ. It is also very possible that this school room model could just be some romantic notion, a utopian ideal based on no recorded system. The bottom line is that the fate of American education, particularly in urban areas, has long abandoned the days where it is just limited to the classroom.

Since the Bush Administration’s No Child Left Behind Act in 2001, which established national academic standards, the United States Congress in conjunction with the United States Department of Education has been trying to remedy the inequalities in schools across the country. The fact remains that American education, which operates mainly within the public sector, is based on school districts with varying financial endowments and different benchmarks for scholastic achievement and institutions with a significant population of minority students have perennially found themselves at the lower end of the spread.

By now the horror stories about inner city education have been quite ubiquitous. Students of color are attending crumbling schools. The achievement gap for between Blacks and White is alarmingly wide. African-Americans don’t have access to the quality of education that could get them in the nation’s top colleges. It is generally recognized that United States’ urban population, especially areas with a high concentration of minority students, suffer the most from this disparity. But acknowledging the inequalities in schools where the student body comprises mostly of children of color means, acknowledging the social factors—teacher quality, student economic background, education of parents, health care, school resources to name a few--that cause these inequalities. It is this end, determining the reasons behind these imbalances, that has fueled debates over the past few years.

One of the places in which this dialogue on education has reached full throttle is New York City. In the past couple of years, Mayor Michael Bloomberg has been working hard to follow the national trend of data driven evaluation of school districts which has been met with some resistance. In a New York Times article, in which Bloomberg announced that student test scores may factor in teacher tenure, many educators wrote back expressing their disapproval for proposed policy. One teacher, who found the proposal less than ideal, wrote, “There are many internal and external factors that influence each student’s learning that are beyond the teacher’s control. Factors related to economics, language, home environment, motivation, attitude and aptitude help inspire or discourage learning. It is not as simple as a test score.”Another teacher wrote, “When I taught the highest-performing class, my average reading score jumped about two years; when I taught the most challenging class, it moved about nine months. The effort was the same, but the results were very different. Should I have been granted or denied tenure?”

The United Federation of Teachers agrees with these positions as well. The New York City teacher’s union holds the belief that linking teacher tenure to test scores would prove stifling for those teachers who work in high needs environments. These are the very environments in which New York City traditionally has experienced personnel shortages. “One-third of new teachers leave teaching before ever coming up for tenure,” UFT president, Randi Weingarten, testified to City Council Education Committee. “Among those thousands we lose, there are a lot more people who could have been great teachers had we given them a little more encouragement and support. Rather than focus on how to keep good teachers, the school system is scaring them away.”

In 1990, Wendy Kopp, a senior at Princeton University’s Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, founded Teach for America, a national non-profit organization which accepts recent graduates from competitive colleges and universities across the country for teaching positions in low-income districts. These young, uncertified teachers go through expedited training and fulfill a two-year requirement with the program. In 2000, New York City addressed its own teacher vacancies with the establishment of the New York City Teaching Fellows, which also recruits recent graduates as well as career changers to teach in the city’s most challenging districts.

Having bright, ambitious individuals teach in areas that many educators have either abandoned or are reluctant to relocate seems like a brilliant initiative on paper, but factor in the inexperience and high turnover rates (many matriculants in TFA and New York City Teaching Fellows leave teaching in less than five years) and many of the issues that these programs sought out to quell are left unresolved. Not only are these teachers dealing with a brand new profession, but they are dealing with scant resources, behavior problems, low skill levels, poor households, and other social ills that are beyond their power.

“Some of these students lack a lot of structure in their home life, and I don't think that teachers are the solution to every problem these kids face,” says Taylor Block, who was trained in the Teaching Fellows Program for three months before teaching in the Bronx. “Schools need to adopt better more consistent school wide disciplinary protocols and have more counselors on staff. It would also help to get the community and the parents involved, so the kids have plenty of support.”

The recession of the late 2000s has further complicated things. Instead of providing an influx of capital to underfunded schools, state budgets were forced to make cuts to their education departments. In 2008, Mayor Bloomberg oversaw a $180 million cut to New York City’s department of education, which resulted in school budgets being trimmed down by an average 1.75% or $70,000 per school.

Principals and teachers have felt the pangs of these reductions on several levels. Many after-school programs had to close their doors. Music and arts curricula have become burdensome vestiges. Schools across the country have had to increase their class sizes and lay off teachers. In 2007, the Title I program, America’s largest source of federal aid to low-income school districts received no additional funding for the 2008-2009 school year. Last year, Mayor Bloomberg enacted a hiring freeze on the Department of Education, restricting principals only to hiring within city’s “rubber room”, or Teacher Reassignment Center which houses pool of teachers awaiting hearing for either misconduct or incompetency. On May 27, 2009, Joel Klein, chancellor of the New York City public school announced $405 million more budget cuts for the 2010 school year.

As a result of reductions in funding, New York has been suffering from overcrowded schools more than ever. In the last few years, the city made national headlines with its project to address the problem by replacing large failing schools with smaller ones. Currently 42% of public and charter school buildings in New York house more one school. Though this measure has reduced student population, it has not reduced class size since, contractually, New York teachers can be assigned to as much as 34 students in one room.

“No one likes budget cuts, especially me, but these are tough times, and education makes up one third of the City’s budget,” say Joel Klein. “Our goal is to keep cuts away from classrooms as much as possible but we can’t find all the necessary savings outside of our schools.”

Bloomberg has recently proposed putting a one-year limit on the amount of time excessed teachers can remain on the payroll to stop the hemorrhaging $80 million a year the Department of Education spends paying teachers who aren’t teaching.

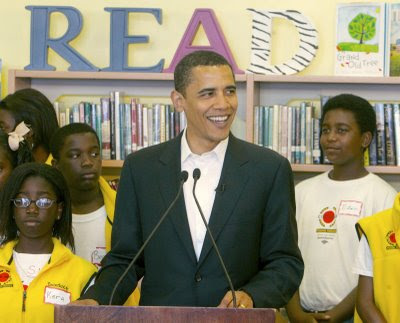

In addition to district movements, the Obama Administration has also been working hard on a national level to pump funding back into state budgets. The administration’s newest initiative is the Race to the Top Fund, which piggybacks off of No Child Left Behind and offers grants to states which show progress and innovation in education. “And the idea here is simple: Instead of rewarding failure, we only reward success. Instead of funding the status quo, we only invest in reform--,” President Obama remarked during January’s State of the Union address. “Reform that raises student achievement; inspires students to excel in math and science; and turns around failing schools that steal the future of too many young Americans, from rural communities to the inner city.”

The national competition, spearheaded by Secretary of Education, Arne Duncan, rewards qualifying states with 4.35 billion dollar incentive for the 2010-2011 school year. States must apply for limited grants and demonstrate success in four reform areas outlined under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, which include establishing college and career-ready standards, implementing data systems to plot student progress, making improvements in teacher effectiveness, and providing intensive support for the lowest-performing schools.

Proponents of the act like David Johns, Senior Policy Advisor to the US Senate and former educator, embrace the country’s shift toward data-driven evaluation. “Data is essential to being able to understand how instruction is impacting learning,” says Johns. “As a former teacher, every day I needed to have some tangible way of knowing what I was trying to convey to my students was being received.”

While Johns, who now works for the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions under Senator Tom Harkin (D) from Iowa, helped draft and approve the ARRA and Race to the Top, he assures that policy makers have weighed the pros and cons of the government’s increased reliance on data. “There is no way to ignore the factors that contribute to why some students aren’t able to achieve as much as others,” he adds. “The challenge is balancing the practical realities that kids live in with the political realities.”

Race to the Top strict requirements also encourage the creation and nurturing of charter schools, which has found many states, adjusting its standards to gain eligibility. New York City, which caps its number of charter schools at 200, has considered lifting the quota to attain the federal funds, a move, which for now, remains a point of contention among district politicians.

“The creation of new charter schools is displacing public schools that are already firmly established in communities,” says Congresswoman Yvette Clarke who represents New York’s 11th Congressional District. “I believe that providing funding for school construction, as a companion to educational reforms, will be a necessary component to future educational reforms.”

Joel Packer, executive director for the Committee for Education Funding also makes it clear that although Race to the Top’s monetary boost presents a temporary solution, he eventually looks forward to programs which cater to the whole child. He cites organizations like the Harlem Children Zone in East Harlem, a pioneering non-profit organization which services low-income families through parenting workshops, parenting workshops, and health programs for its students as a successful model of community education.

“Children are facing these other realities and other needs,” Packer adds. “Yes we need we need to make kids have up-to-date access to textbooks and technology, but we also need to make sure that they’re healthy and safe and well fed.”

The United States Student Association, the largest student run organization in America, has taken solution models to another plateau, lobbying for more grant money for minority students in higher education. The organization, led by legislative director, Angela Peoples, recently helped organized a conference which took place in Washington, DC this March where students discussed major breakthroughs in funding for higher education like the Obama administration’s Student Aid Reform. The bill, which proposes taking away money that has traditionally gone to banks and lenders and issuing student loans straight from the federal budget, would save $87 million for the Pell Grant, a program which helps low income families pay for college. The USSA recently participated in a demonstration in March to augment the Grant’s endowment to 87 million.

“Students are coming together to increase funding for traditionally underrepresented communities,” says Peoples.

With the keys legislative events to take place, the general sentiment in the field of education policy points towards undoing the harms of the recession.

“The Obama administration led the charge for education programs.” assures Packer, “They’re designed to go to states, colleges, school districts to prevent job losses, program cuts, and mitigate tuition increases.”

i7h27m0v78 r4w39h9y19 i7u71x2f88 m7i27j5i97 u2e05r0d99 w0o24h2f42

ReplyDelete