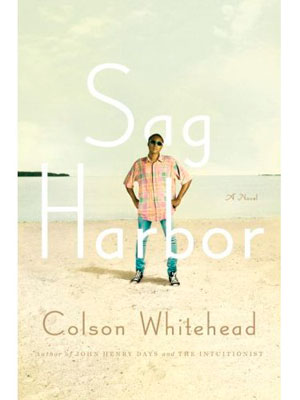

Black to the Beach

By Sidik Fofana—SeeingBlack.com Contributing Editor

The scene in Colson Whitehead’s third novel, Sag Harbor, which epitomizes the main character, Benji, and his rag tag bunch of adolescent companions, arrives when a parentless summer house prompts Benji to break down his friends’ smack-talking rituals. With a stroke of astuteness and whimsicality, Whitehead’s awkward 15-year-old protagonist provides his analysis:

“You could also preface things with a throat-clearing ‘You f*ckin’ as in “You f*ckin’ Cha-Ka from Land of the Lost-lookin’ motherf*cker’…’You f*ckin’ acted as a rhetorical pause, allowing the speaker a few extra seconds to pluck some splendid modifier out of the invective ether, and giving the listener a chance to gird himself for the top-notch put-down/splendid imagery to follow.”

The excessive profanity does not depict this enclave of Black teenagers who vacation in Long Island’s Sag Harbor as hip and in-the-know youngsters growing up during hip-hop’s golden age as much as it depicts them as middle class wannabees who overcompensate for their sheltered lives. It is still laudable, however, that despite the group’s pretensions of independence and knowledge of hip-hop urbanomics, Benji is the one member of the crew who is strangely unapologetic about his well-off, eclectic background. This isn’t more evident than at Sagaponack beach where Benji tries to convince his buddy, Marcus, that Afrika Bambaataa bit his seminal classic “Planet Rock” from a German band, Kraftwerk. He braves the backlash (one, for the blasphemy of implying Afrika Bambataa committed the ultimate Hip-Hop sin of biting and two, for indirectly admitting to his friends that he listened to white music), and offers a comfortable take on his point of view, “I just knew that it was okay to like both Afrika Bambaataa and Kraftwerk, and I liked what Afrika did with Kraftwerk.”

Sag Harbor, according to the author, has no defined plot. Rather than an epic coming-of-age work about one fateful summer, the novel is a slice-of-life that includes events sometimes connected to a larger narrative web (for example when a chance visit from Roxanne Shante and U.T.F.O. at Benji’s place of employment settles a brewing dispute over a word in Melle Mel’s “The Message”) and at other times completely random (when Benji accidentally gets hit in the eye during a BB gun war). The Long Island suburb that serves as the book’s setting becomes Shakespeare’s proverbial stage where Benji and his circle of hormonal and insecure teenage peers fret and strut only to flick off the lights in their vacation homes and return home to another drab school year.

With Junot Diaz winning the Pulitzer prize last year and a Victor Lavalle novel due later this month, Colson Whitehead has re-established himself as a contemporary voice of color. Sag Harbor> paves its own road because it addresses issues of class and race that have proven to be the stuff of great literary works, and it’s not written from a victimized standpoint. Colson Whitehead’s protagonist proudly represents that legion of middle class Blacks in limbo between the singe of being a “minority” and the welcoming hubbub of privilege.

I disagree. Seriously. Will expound later in meeting.

ReplyDeletecheap jordans

ReplyDeletejordan 4

curry 8

bape

golden goose superstar

kobe

balenciaga sneakers

canada goose jacket

pg 1

jordans shoes